GK:1.2.2 Mountainous Terrain of the Korean Peninsula

Geography of Korea: I. Natural Environment > 2. Topography > 2) Mountainous Terrain of the Korean Peninsula

목차

2) Mountainous Terrain of the Korean Peninsula

(1) Korea’s Gyeongdongseong Topography and Mountain Ranges

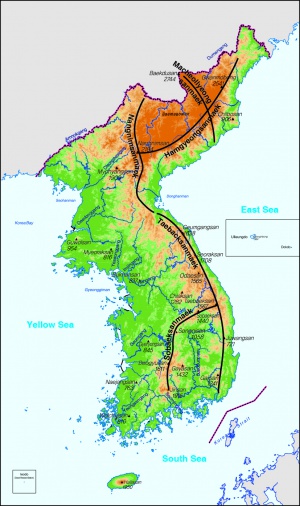

The topography of the Korean Peninsula is characterized by the so-called “gyeongdongseong” (“inclining nature”) that has served to form its primary relief feature. As its name implies, this gyeongdongseong topography is characterized by fault action resulting in a terrain that inclines towards one direction, resulting in a steep and relatively uniform sloping on one side and asymmetrical but mild sloping on the other. Representative examples of this are the north-south extending Taebaeksanmaek and Nangnimsanmaek Ranges and the Hamgyeongsanmaek Range that stretches northeast-southwest (see Figure 1-2).

Taking as an axis the north-south line formed by the Taebaeksanmaek and Nangnimsanmaek Ranges, the eastern slope of these mountains is precipitous, while their western slopes are asymmetrical and relatively mild. The major rivers originating in the Taebaeksanmaek and Nangnimsanmaek Ranges, such as the Cheongcheon, Daedong, Imjin, and Han Rivers, follow the gradual slope and flow westward to empty into the Yellow Sea. Similarly, the southeastern slope of the Hamgyeongsanmaek Range is characterized by its steepness while its northwestern slope descends gradually into Manchuria. Some fairly large rivers, such as the Jangjin, Bujeon, Heocheon, and Seodusu originate in the Hamgyeongsanmaek Range, flowing northward to empty into the Yalu (Amnok) and Tumen (Duman) Rivers.

The gyeongdongseong-style movements of the Korean Peninsula have also had a profound impact on the shape of its coastlines. The Taebaeksanmaek and Hamgyeongsanmaek Ranges that make up Korea’s eastern coast are characterized by the uniform abruptness of their uplifted topography, while the peninsula’s western coast is generally characterized by its low terrain, a situation that has resulted in extreme tidal ranges and irregular shorelines. Because rivers with outlets on the Yellow Sea have such extreme tidal ranges, they do not form deltas and their estuaries spread out like a trumpet. The shape of these rivers’ outlets is thus termed “samgakgang” (lit. triangular river).

Besides the gyeongdongseong movements, it is worth pointing out the Macheollyeongsanmaek and Sobaeksanmaek Ranges for the large influence they have had on the peninsula’s topography. The Macheollyeongsanmaek Range begins at Mt. Baekdu (2744m), Korea’s highest mountain, and follows a direction from north-northwest to south-southeast to the eastern coastal city of Seongjin (now Kimchaek). This range, a string of towering peaks that includes Baekdusan, Bukpotae (2389m), Nampotae (2435m), Daeyeonjibong (2360m), and Duryun (2309m), was formed by the volcanic activity along the Baekdu volcanic range.

The Sobaeksanmaek Range originates around Mt. Taebaek (1567m) where it divides from the Taebaeksanmaek Range and continues in an east-northeast to south-southwest direction to the vicinity of Mt. Songni, where it turns and then progresses from a north-northeast to south-southwest direction. Due to the consistently high peaks of this range, which include Sobaek (1439m), Songni (1058m), Minjuji (1242m), Deokyu (1614m), and Jiri (1915m), it effectively geographically separates the Yeongnam region (i.e., Korea’s two Gyeongsang-do provinces in the southwest corner of the peninsula) from the rest of the peninsula. The Sobaeksanmaek Range distinctness is believed to lie in its formation by tectonic movements.

The peaks that stretch westward from the Taebaeksanmaek and Nangnimsanmaek Ranges are relatively low and broken. The reason for this is has to do with long-term erosion processes of the Korean Peninsula, which have exposed watersheds between the peninsula’s major rivers. Therefore, these mountains may be characterized as being formed through land uplift, a fact clearly discernible in their landforms, and cannot be properly classified as mountains.

Mountainous areas comprise about seventy percent of the Korean Peninsula. However, most of these mountains are relatively low in altitude. In terms of altitude, only 4 percent of Korea’s mountains are higher than 2000 meters, while about 13 percent are between 1000 and 2000 meters, 19 percent between 500 and 1000 meters, 40 percent between 100 and 500 meters, thus over half of Korea’s mountains are below 500 meters in height. In terms of altitude, peaks in the peninsula’s north and along its eastern coast are high, while they grow lower as one proceeds west and south, with the higher peaks concentrated in the major mountain ranges. The Kaema Plateau (Gaema gowon) is situated to the north of the Hamgyeongsanmaek Range and to the east of the Nangnimsanmaek Range. At around 1500 meters, the plateau is termed the “roof of the Korean Peninsula,” and all of the peninsula’s peaks with altitudes higher than 2000 meters are scattered around this region.

(2) Plateaus and Erosion Basins

Viewed from the eastern coast, the Taebaeksanmaek and Hamgyongsanmaek Ranges would appear like towering folding screens. However, the relief features on these ranges are fairly uniform, with few ups and downs as one proceeds to the summit; their slopes are fairly gentle and interspersed with plateaus termed alpine plateaus, high altitude plateaus, or flat summits (Figure 1-3). The high altitude plateaus in the vicinity of where the Yeongdong Highway traverses the Daegwallyeong Pass in Gangwon-do province along Korea’s eastern coast are used for pasturage or for alpine farming. The largest alpine plateau in Korea is the aforementioned Kaema Plateau, which sprawls to the northwest of the Hamgyeongsanmaek Range.

As far as the central peninsula, moving westward from the watershed, as the elevation gradually decreases some alpine plateaus can be found, such at around the 1000-meter altitude of the Taebaeksanmaek Range, at around 600–700 meters in the vicinity of Chungju city, and at around 500 meters on Seoul’s Namhansanseong. High altitude plateaus can also be found along the upper reaches of major rivers flowing into the East Sea.Though the landscape to the east of Chungju and Wanju is rugged and mountainous, the area to the west is scattered with many low-altitude hills. Reaching only around 50 meters in height and with very moderate slopes, this area has been largely developed for agricultural purposes. This terrain is called low altitude plateau. These low altitude plateaus were largely formed from the erosion of high altitude plateaus, and are distributed widely, particularly in granite zones. In the region of the Yellow Sea coast the low altitude plateau is lower yet, sitting at around 25 meters. This landscape, also known as peripheral peneplain, was rapidly developed and cultivated due to the fact that it exhibits little topographical upheaval, comprising as it does the more gradual western slope of Korea’s gyeongdongseong topography.

Erosion basins have been formed through differential erosion along the upper and middle sections of Korea’s major river systems. Chungju, Wonju, and Jecheon on the basin of the South Han River, Chuncheon on the basin of the North Han River, and Daejeon, Okcheon, and Geumsan on the Geum River basin are examples of cities that have been established on both large and small erosion basins. Erosion basins are usually formed in the granite zone, typically surrounded by mountains composed of metamorphic rock.