"Korea's Religious Places - 1.1.3 Haeinsa Temple (Hapcheon, Gyeongsangnam-do)"의 두 판 사이의 차이

(새 문서: ==Haeinsa Temple (Hapcheon, Gyeongsangnam-do)== The key feature of Haeinsa Temple, the temple of the “Ocean-Seal Absorption,” is the 80,000 wooden printing blocks used to print t...) |

잔글 (→Haeinsa Temple (Hapcheon, Gyeongsangnam-do)) |

||

| 1번째 줄: | 1번째 줄: | ||

==Haeinsa Temple (Hapcheon, Gyeongsangnam-do)== | ==Haeinsa Temple (Hapcheon, Gyeongsangnam-do)== | ||

| − | The key feature of Haeinsa Temple, the temple of the “Ocean-Seal Absorption,” is the 80,000 wooden printing blocks used to print the complete Buddhist scripture, in English called the Tripitaka Koreana. Not only are the 80,000 wood blocks a UNESCO World Heritage Treasure, but the building that houses the printing blocks is also unique. There are two parallel buildings designed specifically to house the woodblocks; in each one, the south-facing wall has large windows on the upper section and small windows on the lower section. By windows, we mean openings with protective wooden slats that allow air to circulate. On the north-facing walls, the opposite is the case: there are small windows on the top and large windows on the bottom. This configuration enables air to circulate naturally and helps to preserve the woodblocks. | + | The key feature of Haeinsa Temple, the temple of the “Ocean-Seal Absorption,” is the 80,000 wooden printing blocks used to print the complete Buddhist scripture, in English called the ''Tripitaka Koreana''. Not only are the 80,000 wood blocks a UNESCO World Heritage Treasure, but the building that houses the printing blocks is also unique. There are two parallel buildings designed specifically to house the woodblocks; in each one, the south-facing wall has large windows on the upper section and small windows on the lower section. By windows, we mean openings with protective wooden slats that allow air to circulate. On the north-facing walls, the opposite is the case: there are small windows on the top and large windows on the bottom. This configuration enables air to circulate naturally and helps to preserve the woodblocks. |

| − | Irrespective of the science surrounding the creation of the storehouse for the 80,000 printing blocks for the Tripitaka Koreana, the visit to the temple is an inspiration for Buddhists and non-Buddhists alike. The temple itself is located on the high slopes of Mt. Gayasan. About 100 meters below where the stairs of the temple begin there is a gate. This gate has the name of the mountain and the name of the temple on it—Gayasan Haeinsa. It’s always that format: -san means mountain, and -sa means temple. Temples are part of the mountain and the mountain is part of the temple. This gate has no walls. We do not leave the secular world behind all at once; we progress deeper into the sacred in segments through a series of gates. | + | Irrespective of the science surrounding the creation of the storehouse for the 80,000 printing blocks for the ''Tripitaka Koreana'', the visit to the temple is an inspiration for Buddhists and non-Buddhists alike. The temple itself is located on the high slopes of Mt. Gayasan. About 100 meters below where the stairs of the temple begin there is a gate. This gate has the name of the mountain and the name of the temple on it—Gayasan Haeinsa. It’s always that format: -''san'' means mountain, and -''sa'' means temple. Temples are part of the mountain and the mountain is part of the temple. This gate has no walls. We do not leave the secular world behind all at once; we progress deeper into the sacred in segments through a series of gates. |

| − | [[File:UKS06_Korea's Religious Places_img_22.jpg|500px|thumb|center|Haeinsa Temple and the reenactment of the procession to transport the Tripitaka Koreana]] | + | [[File:UKS06_Korea's Religious Places_img_22.jpg|500px|thumb|center|Haeinsa Temple and the reenactment of the procession to transport the ''Tripitaka Koreana'']] |

| − | After passing through the gate of the Four Heavenly Kings, we climb more stairs and cross another gate, called either the haetalmun, “gate of separation from the world,” or the burimun, “gate of non-duality,” to find ourselves in the lower courtyard. To the left we see the elevated platform housing the four percussion instruments: the drum, the gong, the fish, and the bell, each rung in succession to call all living beings to worship. | + | After passing through the gate of the Four Heavenly Kings, we climb more stairs and cross another gate, called either the ''haetalmun'', “gate of separation from the world,” or the ''burimun'', “gate of non-duality,” to find ourselves in the lower courtyard. To the left we see the elevated platform housing the four percussion instruments: the drum, the gong, the fish, and the bell, each rung in succession to call all living beings to worship. |

After more stairs and another gate, we ascend to the main courtyard. Here is the pagoda that tells us we are in the main compound. But here, unlike most temples, we have to climb a set of stairs, a rather long and steep set, but here there is no gate at the top. | After more stairs and another gate, we ascend to the main courtyard. Here is the pagoda that tells us we are in the main compound. But here, unlike most temples, we have to climb a set of stairs, a rather long and steep set, but here there is no gate at the top. | ||

| − | The main hall on the north end of the compound here is dedicated to Vairocana, who displays the wisdom fist mudra. Here at this temple where the Tripitaka is stored and protected, one would think this should be Shakyamuni, but Vairocana, the Buddha symbolizing the universe, as it is, who is accessible through the Ocean-Seal Absorption, is the main Buddha of this temple associated with the Hwaeom Order. The temple’s connection with Vairocana predates the carving of the blocks. As for that matter, the blocks were not carved here; rather, they were carved at a temple on Ganghwado Island, perhaps at Jeondeungsa Temple. | + | The main hall on the north end of the compound here is dedicated to Vairocana, who displays the ''wisdom fist'' mudra. Here at this temple where the Tripitaka is stored and protected, one would think this should be Shakyamuni, but Vairocana, the Buddha symbolizing the universe, as it is, who is accessible through the Ocean-Seal Absorption, is the main Buddha of this temple associated with the Hwaeom Order. The temple’s connection with Vairocana predates the carving of the blocks. As for that matter, the blocks were not carved here; rather, they were carved at a temple on Ganghwado Island, perhaps at Jeondeungsa Temple. |

<gallery align="center" widths="400px" heights="400px"> | <gallery align="center" widths="400px" heights="400px"> | ||

File:UKS06_Korea's Religious Places_img_24.jpg|Jeongjungtap Pagoda and Daeungjeon Hall (behind) of Haeinsa Temple | File:UKS06_Korea's Religious Places_img_24.jpg|Jeongjungtap Pagoda and Daeungjeon Hall (behind) of Haeinsa Temple | ||

| − | File:UKS06_Korea's Religious Places_img_23.jpg|The Tripitaka Koreana | + | File:UKS06_Korea's Religious Places_img_23.jpg|The ''Tripitaka Koreana'' |

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

2017년 1월 17일 (화) 22:54 판

Haeinsa Temple (Hapcheon, Gyeongsangnam-do)

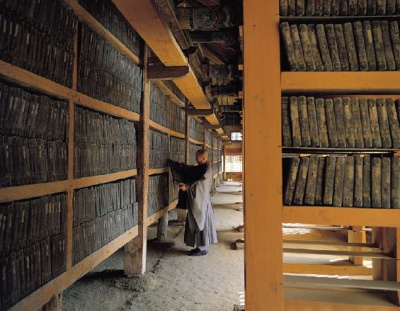

The key feature of Haeinsa Temple, the temple of the “Ocean-Seal Absorption,” is the 80,000 wooden printing blocks used to print the complete Buddhist scripture, in English called the Tripitaka Koreana. Not only are the 80,000 wood blocks a UNESCO World Heritage Treasure, but the building that houses the printing blocks is also unique. There are two parallel buildings designed specifically to house the woodblocks; in each one, the south-facing wall has large windows on the upper section and small windows on the lower section. By windows, we mean openings with protective wooden slats that allow air to circulate. On the north-facing walls, the opposite is the case: there are small windows on the top and large windows on the bottom. This configuration enables air to circulate naturally and helps to preserve the woodblocks.

Irrespective of the science surrounding the creation of the storehouse for the 80,000 printing blocks for the Tripitaka Koreana, the visit to the temple is an inspiration for Buddhists and non-Buddhists alike. The temple itself is located on the high slopes of Mt. Gayasan. About 100 meters below where the stairs of the temple begin there is a gate. This gate has the name of the mountain and the name of the temple on it—Gayasan Haeinsa. It’s always that format: -san means mountain, and -sa means temple. Temples are part of the mountain and the mountain is part of the temple. This gate has no walls. We do not leave the secular world behind all at once; we progress deeper into the sacred in segments through a series of gates.

After passing through the gate of the Four Heavenly Kings, we climb more stairs and cross another gate, called either the haetalmun, “gate of separation from the world,” or the burimun, “gate of non-duality,” to find ourselves in the lower courtyard. To the left we see the elevated platform housing the four percussion instruments: the drum, the gong, the fish, and the bell, each rung in succession to call all living beings to worship.

After more stairs and another gate, we ascend to the main courtyard. Here is the pagoda that tells us we are in the main compound. But here, unlike most temples, we have to climb a set of stairs, a rather long and steep set, but here there is no gate at the top.

The main hall on the north end of the compound here is dedicated to Vairocana, who displays the wisdom fist mudra. Here at this temple where the Tripitaka is stored and protected, one would think this should be Shakyamuni, but Vairocana, the Buddha symbolizing the universe, as it is, who is accessible through the Ocean-Seal Absorption, is the main Buddha of this temple associated with the Hwaeom Order. The temple’s connection with Vairocana predates the carving of the blocks. As for that matter, the blocks were not carved here; rather, they were carved at a temple on Ganghwado Island, perhaps at Jeondeungsa Temple.

The carving of the texts is a highly technical matter, beginning with the kind of wood to be selected. Birch and cherry wood are the favorites. Then the wood has to be aged so that it won’t twist and warp as years go by. The timber is first soaked in salt water for three years; then, set out to dry for three years before they begin cutting the blocks and ultimately carving them. The carving process begins when a piece of paper, lined and filled in with text, usually handwritten, is pasted on the wood face down, and all but the letters of the paper are cut away, leaving a reverse image for printing.

An interesting footnote to one’s visit to Haeinsa Temple can be found as one leaves the upper courtyard. The traffic pattern takes visitors over to the west side of the compound to leave. To work one’s way back to the main courtyard and to leave the temple, one goes past an old tree on a rise off the side of the main path. There is a plaque that explains that this tree grew out of the walking staff of Choe Chi-won (857–d. after 908). The story of Choe is remarkable. He left for China as a youth, where he studied the Confucian classics and passed the Tang Dynasty civil service exam. The exam is a recruiting device for government officials, and Choe served the Tang court. He returned to his native Silla in his prime and made himself available for a position. Having served in the Tang government, he should have been a good candidate for an important position in the Silla Kingdom, but such was not the case because political power in the Silla Kingdom was dominated by nobles of high birth. Frustrated, he finally left Gyeongju, the Silla capital, and retired to Haeinsa Temple. Choe Chi-won’s tree is a symbol of both the frustration of a rejected Confucian scholar, and the fact that at least at one level, there is a comfortable harmony of Buddhism and Confucianism in Korea. One final note before we leave Choe Chi-won: we should note that later on, when the Confucians decided to name sages, and they eventually named eighteen sages (to keep up with the sixteen Chinese sages and the four disciples, all together with Confucius, himself) to be honored in the national academy and in every county school in Korea, Choe was the second sage honored.