"Korea's Religious Places - 1.1 Characteristics: A Who's Who at a Buddhist Temple"의 두 판 사이의 차이

| 182번째 줄: | 182번째 줄: | ||

Beopjusa Temple is a temple dedicated to the spirit of Maitreya, the future Buddha. Most temples feature one of the three as the primary Buddha: Shakyamuni, Amitabha, or Vairocana, but here the main figure is the Buddha of the future, Maitreya. Buddhist traditions teach that not only is Maitreya a Buddha yet to come, but he represents hope for those in this life as well. | Beopjusa Temple is a temple dedicated to the spirit of Maitreya, the future Buddha. Most temples feature one of the three as the primary Buddha: Shakyamuni, Amitabha, or Vairocana, but here the main figure is the Buddha of the future, Maitreya. Buddhist traditions teach that not only is Maitreya a Buddha yet to come, but he represents hope for those in this life as well. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <gallery align="center" widths="400px" heights="400px"> | ||

| + | File:UKS06_Korea's Religious Places_img_27.jpg|Daeungbojeon Hall | ||

| + | File:UKS06_Korea's Religious Places_img_28.jpg|Buddha for National Unification at Beopjusa Temple | ||

| + | </gallery> | ||

| + | |||

The temple was founded in 553 by a monk named Uisin, who founded it after returning from a trip to China. The temple name, Beopju, means “where the dharma abides” because the temple once housed the manuscripts or sutras that Uisin brought back from China. | The temple was founded in 553 by a monk named Uisin, who founded it after returning from a trip to China. The temple name, Beopju, means “where the dharma abides” because the temple once housed the manuscripts or sutras that Uisin brought back from China. | ||

2017년 1월 3일 (화) 22:09 판

목차

- 1 Bulguksa Temple (Gyeongju, Gyeongsangbuk-do)

- 2 Seokguram Grotto (Gyeongju, Gyeongsangbuk-do)

- 3 Haeinsa Temple (Hapcheon, Gyeongsangnam-do)

- 4 Jogyesa Temple (Seoul)

- 5 Tongdosa Temple (Yangsan, Gyeongsangnam-do)

- 6 Beopjusa Temple (Boeun, Chungcheongbuk-do)

- 7 Magoksa Temple (Gongju, Chungcheongnam-do)

- 8 Seonamsa Temple (Suncheon, Jeollanam-do)

- 9 Daeheungsa Temple (Haenam, Jeollanam-do)

- 10 Buseoksa Temple (Yeongju, Gyeongsangbuk-do)

- 11 Bongjeongsa Temple (Andong, Gyeongsangbuk-do)

- 12 Songgwangsa Temple (Suncheon, Jeollanam-do)

Major Buddhist temples have multiple buildings, each dedicated to a specific Buddhist image. A larger temple complex will typically have a building for most, if not all, of the following: Shakyamuni (Seokgamoni), Amitabha (Amita), Vairocana (Birojana), Maitreya (Mireuk), Avalokiteshvara (Gwanseeum), and the mountain god (sansin, as san means mountain and sin means god). Sometimes there are halls dedicated to other Buddhist figures. At the entrance to the temple complex there is often a building that is also a gate that houses the Four Heavenly Kings, but they are in reality guardians of the four directions. There is also a structure, with only a roof but open on the sides, that houses the four percussion instruments that are rung or struck at dawn and at sunset, and in some places at midday.

These are the main features at most temple complexes. Let us examine each in a generic sense and propose a kind of template that will contain much of what is found at a Buddhist temple, and then when we look at the major Buddhist temples, we can plug each element of the temple into this template.

The hall dedicated to Shakyamuni is the main hall at most temples, although some temples will feature Amitabha or Vairocana as the figure in the main hall, and a few will have Maitreya. If the hall is dedicated to Shakyamuni, the hall is titled the “hall of the great hero” (daeungjeon). Sometimes there are three figures in the main hall, and sometimes there are five or seven. At times, the three major Buddhas will be flanked by two or four bodhisattvas.

If there is a hall for Amitabha, the hall will be titled the “hall of extreme bliss” (geungnakjeon). The hall for Vairocana is often simply called the “hall of Vairocana” (birojeon).

A Buddha can often be identified by the particular mudra, or hand sign, that he uses. For example, Shakyamuni will often be depicted touching his knee with his fingers extended so that they almost touch the ground, to symbolize that he is calling on the earth to witness that he is the enlightened one—indeed, that is the meaning of Buddha. In Korea, Vairocana is usually seen holding his right hand cupped around the extended finger of the left hand, or with his right hand covering the row of knuckles of his left hand. This is called either the wisdom fist or the union of male and female principles.

<galleryy align="center" widths="400px" heights="400px">

File:UKS06_Korea's Religious Places_img_10.jpg|Geungnakjeon Halls at Eunjeoksa Temple, Yeosu

File:UKS06_Korea's Religious Places_img_9.jpg|Yongguksa Temple, Uiryeong

File:UKS06_Korea's Religious Places_img_11.jpg|A Buddha can often be identified by the particular mudra, or hand sign.

File:UKS06_Korea's Religious Places_img_12.jpg|Haesugwaneumsang (Goddess of Mercy) at Naksansa Temple, Yangyang

</gallery>

Bodhisattvas are usually standing, whereas Buddha images are seated. Avalokiteshvara (Gwaneum or Gwanseeum), perhaps the most-seen bodhisattva, is usually depicted standing and wearing an elaborate crown, and is often depicted with multiple additional heads, miniature heads on the crown of his head. The bodhisattva is often shown in an eleven-faced form or a thousand-handed form. He also has necklaces and lacey robes. Because of the dress and jewelry, and also the idea that this bodhisattva is known for being merciful and good for answering prayers, many assume that she is a woman—“Goddess of Mercy,” she is often called. Historically, this Bodhisattva was Avalokiteshvara, a man. But through the process of becoming a bodhisattva, and taking on the mission of alleviating suffering and answering prayers, he has become female in popular Buddhism because compassion and mercy were conceptualized as female traits in Asia. In an ideal doctrinal sense, Buddhas and bodhisattvas are gender neutral or, rather, have transcended gender distinctions.

Every large-scale temple in Korea has a building that serves as a kind of gatehouse, containing the Four Heavenly Kings. In most cases, they are free-standing statues, often larger than life, in the ten-foot-tall range. They are not exactly the same from temple to temple. Each temple has its own artisans who carve the statues according to their own interpretations, but there are major features for each of the four guardians that signify who they are and which direction—north, south, east, west—they represent.

The north is the Heavenly King Vaisravana (Damun), “he who hears everything,” who holds a spear in one hand and a small pagoda in the other. He tends to have dark skin, either black or blue. The south is Heavenly King Virudhaka (Jeungjang), “he who causes growth,” who holds a sword and is light-skinned. The east is Heavenly King Dhritarashtra (Jiguk), “he who upholds the realm,” who holds a lute and is light-skinned. And the west is Heavenly King Virupaksa (Gwangmok), “he who sees everything,” who holds a dragon in one hand and a jewel in the other. He tends to be dark-skinned.

Each of these deities has a history that not only goes deep in Buddhism, but also has connections with Hinduism, both of which developed simultaneously from Vedic beliefs and traditions in early India. In Hinduism, for example, the deity of the north, Vaisravana, is associated with Kubera, who in an early incarnation as a mortal was a wealthy mill-owner who was known for his wealth, but also for his generosity to the poor.

Inside a temple complex, there is a roofed building without walls that houses the four percussion instruments: the drum, the gong, the wooden fish clapper, and the bell. These are rung twice a day in some temples—morning and evening—and three times a day in others, with a short performance before lunch. First is the drum. The monks take turns beating on the drum and each performer has a slightly different rhythm or nuance. The drum skin is from two cattle, one on each side of the drum; one from a cow and one from a bull, and each had to have died naturally. The drum is beaten to call all living beings of the land to worship the Buddha. The wooden fish has a hollowed-out inside where the monks rattle their wooden sticks. This is to call all the creatures of the waters to worship. Then, the monks beat on the gong; its high-pitched clang calls the creatures of the air to worship. With land, water, and air taken care of, what is the bell for? When the bell sounds its deep mellow tone, the tormentors in hell have to pause and give relief to those they are assigned to torment—the residents of hell who are serving terms of punishment prior to being reborn to see if they can get it right this time.

The historic Buddha of our epoch (the word in Sanskrit is kalpa, roughly an immeasurable period of time during which a high mountain is worn down into a flat plain) is Shakyamuni. As a young man, he was raised in a palace and led a pampered life. Leaving the palace one day he was surprised to see the things his parents were keeping from him—poverty, illness, old age, and death. The reality of his discovery bothered him and he wanted to understand the meaning of these things, but his protective parents barred him from leaving the palace. Miraculously, to leave the palace and begin his search for enlightenment, he flew over the palace walls on his horse, with his servant riding horseback as well.

Out in the world, he tried to discover the way through fasting and asceticism, but that didn’t work. Finally, while meditating under a peepal tree (the Bodhi tree or sacred fig), he achieved enlightenment, and understood the Four Noble Truths, to wit: life is suffering, suffering is caused by desires (or attachment), it is possible to overcome suffering, and it is done by following the Noble Eightfold Path. These four truths became the foundational doctrine of Buddhism.

On his way to enlightenment, the historical Buddha encountered temptations and subjugated the god of illusion, Mara. One of the stories of his overcoming temptation has to do with the temptations of the flesh. Mara’s daughters, three beautiful women, one with a flute, one with a lute, and one singing try to lure him to tarry with them, but he rejects their temptations, and then their beautiful faces fall off, and they are revealed as demons who had only been masquerading as the pleasures of the flesh.

The Buddha was transformed. This transformation is marked in paintings at many temples showing Shakyamuni, now with a halo and the serene look of one who has attained enlightenment. He begins his teaching and attracts disciples. There are many narratives of this phase of his life involving miracles and other manifestations that the Shakyamuni was really a Buddha. When he was cremated, jewels cascaded from the funeral bier, and thus started the tradition of sifting through the ashes of a monk after he dies and is cremated to find jewels.

Such jewels have a special name and devotional practice associated with them. They are called sari, or relics of the body of the Buddha, and are kept in a sariham—in Korean, a case for the relics. The case is then enclosed in a capsule that is enclosed in the base of a pagoda, or a small stone tower. This is the Korean practice. It has its roots in the stupa of India, often a mere earthen mound; sometimes the earthen mound is covered in stone. In China, pagodas can be very tall—multistoried towers often made of brick. In Japan, the archetypal pagoda is made of wood, again often a multi-storied, tall building. Korea has had tall pagodas made of wood, and there are some made of brick, or stone cut to look like the brick of China, but the archetypal pagoda is made of stone and is typically only ten to fifteen feet tall.

Indeed, there is a pagoda in the main courtyard, of the several courtyards, at a temple complex. The main courtyard is in front of the dharma hall (beopdang), of which there is only one at each temple. The dharma hall is the center of the worship at the temple; it is there that the community of resident monks at the temple will meet all together for worship twice a day—at the beginning of the day, before sunrise, and at the end of the day. All the monks meet in the dharma hall to chant and bow, sometimes performing the ritual of the 108 bows, one for each of the foolish things or sins of mankind.

Bulguksa Temple (Gyeongju, Gyeongsangbuk-do)

Bulguksa Temple is a beautiful temple in an exquisite setting. The temple complex has five major halls, ancillary buildings, and gates. Bulguksa Temple is reached by passing through the main gate on the south side of the complex. Along the path of several hundred meters there is a gatehouse for the guardians of the four directions.

As we proceed into the temple compound, we see two beautiful sets of staircases. The main hall in this temple is reached up the stairs to the right, to the east. The smaller staircase to the west leads to the hall of Amitabha (Amita). Behind these two halls are halls dedicated to the bodhisattva of compassion Avalokiteshvara (Gwanseeum), the cosmic Buddha Vairocana, and a hall for the Buddha’s disciples. Let us look at each of these five archetypal halls at Bulguksa Temple, for similar halls are found at other temples.

At Bulguksa Temple, there are two pagodas in the courtyard in front of the main hall. The more attractive one is the Pagoda of Many Treasures (Dabotap Pagoda, National Treasure no. 20). There are several levels of treasures designated by the government (National Treasure is highest, Treasure is second, and third are local area designated treasures). The pagoda is made of stone cut to resemble wood. There are handrails crafted as long, thin cylinders resembling natural wooden poles used in a handrail or balustrade. The rooflines sweep up as if made of wood like those of the temple buildings in the compound. The beauty of this pagoda is captured on the KRW 10 coin in circulation today.

The other pagoda, Shakyamuni Pagoda (Three-story Stone Pagoda, National Treasure no. 21) is a three-story stone pagoda in classic Korean style. On the inside, however, is something unique. Inside each pagoda is a box or container preserving the relics of the Buddha and other treasures to empower the pagoda. In 1966, after thieves attempted to break into the pagoda, the monks discovered a dharani-sutra, what was then the oldest printed paper in the world. Printed sometime before the dedication of the temple complex in 751, the dharani-sutra is a long scroll 6.5 meters long, but only about 6.5 centimeters wide, printed from a set of wooden printing blocks.

These two magnificent pagodas are in the courtyard of the main hall dedicated to Shakyamuni. The hall is titled “Hall of the Great Hero” (Daeungjeon Hall). The smaller staircase, to the west, leads to a secondary courtyard and hall titled the “Hall of Extreme Bliss” (Geungnakjeon Hall). This is the hall of Amitabha (Amita), the Buddha of the Pure Land in the West.

Amitabha is the most popular Buddha in East Asia. A scripture says that when he was a bodhisattva, he vowed that he would not become a Buddha unless he succeeded in keeping forty-eight vows. One of his vows was to save anyone who called on his name for ten moments of thought. What an easy practice! This led to a widespread practice of fervently chanting Amitabha’s name to assure deliverance in his Pure Land in the West.

There is a third Buddha who is also found at Korean temples, Vairocana. His role in the Buddhist pantheon is that of the central cosmic Buddha. There are innumerable Buddhas, and this Buddha is the source of them all.

In the back row, then, the Vairocana Hall is in the center and to its right, behind the main hall, is a hall to Avalokiteshvara, the most popular of all bodhisattvas. Bodhisattvas, by definition, make vows not to enter Nirvana until all living beings—including humans, animals, and hungry ghosts—are liberated from the cycle of rebirth and death. A bodhisattva is an approachable figure to whom people can pray and have some assurance of assistance. Avalokiteshvara, “he who hears the cries of the world,” is often called the “Goddess of Mercy” in East Asia. The hall dedicated to Avalokiteshvara is one of the most visited at the temple complex. Behind the statue of Avalokiteshvara at Bulguksa Temple is a painting showing the bodhisattva in thousand-hand form with eleven faces. Each hand has an eye in its palm, and the hands on the outer circle also hold an implement of one kind or another—each showing that the bodhisattva has power and ability. If a parent is praying that a child will pass an exam, there is a hand with a brush, offering help on the test. If the prayer is for something that can be helped with money, there is a hand with money. If the prayer is to repair something broken, there is a hammer. Each hand has an implement that shows different ways that the bodhisattva can answer prayers. The symbolism of the eleven faces is that the bodhisattva observes the cries of living beings coming from all directions.

In the back row of the temple complex to the left there is one more important hall for prayers. Currently it is a hall of disciples, depicting a dozen or so people from the time of Shakyamuni wearing different clothes to show that they are people from varying walks of life. But before 1984, it was the hall of the mountain god (sansin). The mountain god is the most popular folk deity in Korea. Most large temple complexes have a hall for the mountain god located to the rear of the compound and to the left. Buddhism tends to adopt and adapt native religious beliefs wherever it spreads.

Seokguram Grotto (Gyeongju, Gyeongsangbuk-do)

The highlight of the visit to Bulguksa Temple is nearly three kilometers away, up the hill, and on the far side of the ridge that will lead you to where you can see the East Sea in the distance. Near the crest of the hill looking eastward, inside a man-made cave, sits a ten-foot-tall Buddha carved from a single piece of granite. It would have been impossible to carve the Buddha and move him into the cave; rather, the cave was built around the Buddha.

Buddhist images are associated with caves for a good reason. Buddhism began in India and spread to China via the Silk Road where, amid dangers of thieves and the terrain itself, Buddhas and bodhisattvas functioned as great protective spirits. Along the Silk Road, caves were associated with places of safety for staying overnight, and to increase the safety of such caves they often featured a local deity, or a protective deity. Over the centuries, the appeal and power of Buddhism won out over the local gods. It was cosmopolitan and appealed to people from West Asia to East Asia, from Central Asia to China, to Korea, to Japan. Thus, a Buddha in a cave was one of the first images that came to Korea, and Seokguram Grotto is the finest expression of that sentiment. In effect, Seokguram Grotto is the last stop on the Silk Road as it looks out to the East Sea from the southeastern part of Korea before it ends in the ocean.

- The Great Stone Buddha in Seokguram Grotto (left) and its rendering of interior

The Buddha in Seokguram Grotto is a classic image that shows several of the bodily marks of a true Buddha in the Tang Dynasty style that became widely popular in East Asia. These include the tuft of white hair between the eyebrows, an extended lump on the top of the head, knots of hair on the head, extended earlobes, three rings on his neck, a robe hung over the left shoulder, androgynous breasts, his hands in the position of one of the prescribed mudras, a lotus imprint on the palms of his hands and on the bottoms of his feet, as he sits in a cross-legged lotus position on a lotus pedestal. The Buddha is a classic image, but there is some degree of confusion about who he is. His mudra with his right hand on his knee and his fingers almost touching the earth is the mudra of calling on earth to witness that he is the Buddha. This mudra suggests that he is Shakyamuni, the historic Buddha. However, the perfectly mathematical structure of the grotto suggests that the main Buddha is the Vairocana of the Hwaeom Order, which was popular in the Silla court. The fact that an image of Avalokiteshvara is prominent among the carvings on the wall surrounding the Buddha would indicate that the image is Amitabha. It might be that the artisan, Kim Dae-seong, intentionally blended symbols together, a characteristic of the Hwaeom Order. Work on the grotto-temple ended with the death of the architect Kim Dae-seong in 774.

The remodeling in the 1960s brought new access to Seokguram Grotto. Whereas traditionally a believer had to hike the 2.2 kilometers up the hill to appreciate the cave, now there is a road switching back and forth up the hill for tour buses to make the trip easily. From the parking lot, the last half-mile hike to the cave is on a level path wide enough to accommodate hundreds of tourists and schoolchildren on their field trips. Only the last segment requires hiking now, and that is up a set of stone steps the equivalent of maybe a three- or four-story building. Once, the pilgrimage was part of the experience. Now, it is the great number of visitors that marks the visit to Seokguram Grotto.

Before the construction of the new road and trail, pilgrims could enter the cave, circumnavigate the beautiful stone image, and even reach up and touch him. Now, the cave is closed off from visitors by a glass window; visitors stand outside the actual cave, in an antechamber, where they can view the Buddha only from a distance.

Haeinsa Temple (Hapcheon, Gyeongsangnam-do)

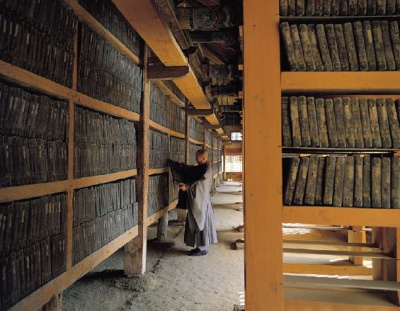

The key feature of Haeinsa Temple, the temple of the “Ocean-Seal Absorption,” is the 80,000 wooden printing blocks used to print the complete Buddhist scripture, in English called the Tripitaka Koreana. Not only are the 80,000 wood blocks a UNESCO World Heritage Treasure, but the building that houses the printing blocks is also unique. There are two parallel buildings designed specifically to house the woodblocks; in each one, the south-facing wall has large windows on the upper section and small windows on the lower section. By windows, we mean openings with protective wooden slats that allow air to circulate. On the north-facing walls, the opposite is the case: there are small windows on the top and large windows on the bottom. This configuration enables air to circulate naturally and helps to preserve the woodblocks.

Irrespective of the science surrounding the creation of the storehouse for the 80,000 printing blocks for the Tripitaka Koreana, the visit to the temple is an inspiration for Buddhists and non-Buddhists alike. The temple itself is located on the high slopes of Mt. Gayasan. About 100 meters below where the stairs of the temple begin there is a gate. This gate has the name of the mountain and the name of the temple on it—Gayasan Haeinsa. It’s always that format: -san means mountain, and -sa means temple. Temples are part of the mountain and the mountain is part of the temple. This gate has no walls. We do not leave the secular world behind all at once; we progress deeper into the sacred in segments through a series of gates.

After passing through the gate of the Four Heavenly Kings, we climb more stairs and cross another gate, called either the haetalmun, “gate of separation from the world,” or the burimun, “gate of non-duality,” to find ourselves in the lower courtyard. To the left we see the elevated platform housing the four percussion instruments: the drum, the gong, the fish, and the bell, each rung in succession to call all living beings to worship.

After more stairs and another gate, we ascend to the main courtyard. Here is the pagoda that tells us we are in the main compound. But here, unlike most temples, we have to climb a set of stairs, a rather long and steep set, but here there is no gate at the top.

The main hall on the north end of the compound here is dedicated to Vairocana, who displays the wisdom fist mudra. Here at this temple where the Tripitaka is stored and protected, one would think this should be Shakyamuni, but Vairocana, the Buddha symbolizing the universe, as it is, who is accessible through the Ocean-Seal Absorption, is the main Buddha of this temple associated with the Hwaeom Order. The temple’s connection with Vairocana predates the carving of the blocks. As for that matter, the blocks were not carved here; rather, they were carved at a temple on Ganghwado Island, perhaps at Jeondeungsa Temple.

The carving of the texts is a highly technical matter, beginning with the kind of wood to be selected. Birch and cherry wood are the favorites. Then the wood has to be aged so that it won’t twist and warp as years go by. The timber is first soaked in salt water for three years; then, set out to dry for three years before they begin cutting the blocks and ultimately carving them. The carving process begins when a piece of paper, lined and filled in with text, usually handwritten, is pasted on the wood face down, and all but the letters of the paper are cut away, leaving a reverse image for printing.

An interesting footnote to one’s visit to Haeinsa Temple can be found as one leaves the upper courtyard. The traffic pattern takes visitors over to the west side of the compound to leave. To work one’s way back to the main courtyard and to leave the temple, one goes past an old tree on a rise off the side of the main path. There is a plaque that explains that this tree grew out of the walking staff of Choe Chi-won (857–d. after 908). The story of Choe is remarkable. He left for China as a youth, where he studied the Confucian classics and passed the Tang Dynasty civil service exam. The exam is a recruiting device for government officials, and Choe served the Tang court. He returned to his native Silla in his prime and made himself available for a position. Having served in the Tang government, he should have been a good candidate for an important position in the Silla Kingdom, but such was not the case because political power in the Silla Kingdom was dominated by nobles of high birth. Frustrated, he finally left Gyeongju, the Silla capital, and retired to Haeinsa Temple. Choe Chi-won’s tree is a symbol of both the frustration of a rejected Confucian scholar, and the fact that at least at one level, there is a comfortable harmony of Buddhism and Confucianism in Korea. One final note before we leave Choe Chi-won: we should note that later on, when the Confucians decided to name sages, and they eventually named eighteen sages (to keep up with the sixteen Chinese sages and the four disciples, all together with Confucius, himself) to be honored in the national academy and in every county school in Korea, Choe was the second sage honored.

Jogyesa Temple (Seoul)

The headquarters temple for almost all of Korea is the Jogyesa Temple in downtown Seoul. There are several sects of Buddhism in Korea, but the dominant sect is called the Jogye Order (Jogyejong). The present-day Jogye Order is the standard-bearer for celibate Buddhism in Korea.

This temple goes back to the founding of the Joseon Dynasty and its move to Seoul in 1394. The temple was enlarged in 1910 at the beginning of the Japanese colonial era. There is Natural Monument no. 9, a large lacebark pine tree on the compound. It was planted by a traveler who brought it back from China, and is over 500 years old. Many temples have well-preserved and noteworthy trees and other plants on the compound. This speaks to the harmony of nature and religion—true of Confucianism and Shamanism as well as Buddhism in Korea.

Surrounding the entrance to Jogyesa Temple, on the main road of Anguk-dong in the heart of Seoul, are various shops selling Buddhist articles including clothes for monks and various images and other things for Buddhist worship. Often it is not only Buddhists who would buy such articles for temples and private worship—Shamans also like Buddhist images and artifacts to equip their Shaman shrines. The harmony of Shamanism and Buddhism is one of the main features of Korean religion.

Across the street from the entrance to Jogyesa Temple is a building housing administrative offices for the Jogye Order. There, one can arrange a temple stay at most of the temples nationwide. In recent years, the practice of staying overnight at a Buddhist temple has grown in popularity. Temples, by their nature, welcome sojourners. This has long been the case, but in recent years, temples have organized temple stays for foreigners and Koreans alike, where one can stay one night, or several nights, and experience a taste of monastic life at a temple.

Tongdosa Temple (Yangsan, Gyeongsangnam-do)

North of Busan, deep in a mountain valley is Tongdosa Temple, one of the “Three Jewel” temples, the temple of the Buddha. Here, there is a small pagoda that houses a relic of the historical Buddha Shakyamuni. One of the many jewels, sarira, that cascaded from his cremated funeral bier was brought to Korea and given to Tongdosa Temple by its founder, the Silla monk Jajang (d. ca 658) in 646. Because this is the temple of the Buddha, rather than having an image of the Buddha in the main hall, there is a window, a long oblong opening in the wall, that looks out at the Adamantine Precepts Platform (Geumgang Gyedan, Ordination Platform) that houses the relic of the Buddha in a pagoda-like structure on the top of the precepts platform.

The main worship hall, the Hall of the Great Hero (Daeungjeon Hall), has been designated a National Treasure—no. 290, one of the more recent designations. The absence of any image of Buddhas and bodhisattvas in the main hall is remarkable for this temple. Everything centers on the Adamantine Precepts Platform, with a pagoda-like structure on the platform in the shape of an overturned cauldron, in which is enshrined the relic of the historical Buddha. At the morning and evening rituals, the monks face the Adamantine Precepts Platform, whereas at all other temples, the monks face the images of one or more Buddhas and often a set of bodhisattvas. Therefore, the atmosphere at Tongdosa Temple is different from that of all other temples. Indeed, Tongdosa means to save the world through the mastery of the Way to enlightenment.

The setting of Tongdosa Temple is like that of the other two jewel temples—Haeinsa Temple, the jewel of the dharma (the Buddhist teachings), and Songgwangsa Temple, the jewel of the sangha (the monastic community). All three are located several kilometers ascent into a canyon, with a beautiful and powerful stream running alongside the path to the temple. Tongdosa Temple occupies many acres of mountainside, including farmland that is farmed by the monks for the sustenance of the monks and visitors.

A temple stay at Tongdosa Temple includes an opportunity to partake of temple food—all vegetarian—in the way monks do, using the four bowls. Monks will partake of their meals, breakfast, lunch, and dinner, in a common room where they sit on the floor, all facing the center of the room. A team of monks will serve the food that each monk will put in the four bowls—one for rice, one for soup, one for various vegetables, and one for water. On a signal, three claps of a split bamboo stick slapped against one’s hand, all will eat. No food is wasted. Using the water in the water bowl, the bowls are rinsed out, dried with a cloth, and then set on the shelf ready for the next meal. Simplicity is the key word for the meal and for all monastic life.

Beopjusa Temple (Boeun, Chungcheongbuk-do)

On the slopes of sacred Mt. Songnisan, which literally means “separated from the secular or mundane world,” not far from Cheongju, sits a beautiful temple complex called Beopjusa Temple. Dating from the Silla period, it has several National Treasures, including National Treasure no. 5, the Twin Lion Stone Lantern, a stone lantern supported by two lions standing on their back legs. There is also a tall wooden pagoda that is five stories tall (pagodas are always an odd number of stories tall): National Treasure no. 55, the Palsangjeon Wooden Pagoda.

There is a stately old pine tree there that is called Songni Jeongipumsong Pine Tree (the Pine Tree of Government Rank Senior 2). Ranks were only given to officials in the government, starting with a junior nine rank, then working up through senior nine, junior eight, senior eight, on up to senior one rank. For a pine tree to be a senior two rank is very high. There is a story. When King Sejo (r. 1455–1468) traveled to Beopjusa Temple on a royal excursion in 1464, as he passed by, the tree branches bowed to his carriage chair. He stopped and got off the carriage, whereupon the branches of the tree rose up, as if to offer protection as he approached. He was so impressed with the loyalty and dignity of the tree that he promoted it on the spot to the second rank in the government! It is the only tree, in fact the only non-human, to ever be so honored.

Beopjusa Temple is a temple dedicated to the spirit of Maitreya, the future Buddha. Most temples feature one of the three as the primary Buddha: Shakyamuni, Amitabha, or Vairocana, but here the main figure is the Buddha of the future, Maitreya. Buddhist traditions teach that not only is Maitreya a Buddha yet to come, but he represents hope for those in this life as well.

The temple was founded in 553 by a monk named Uisin, who founded it after returning from a trip to China. The temple name, Beopju, means “where the dharma abides” because the temple once housed the manuscripts or sutras that Uisin brought back from China.

As a temple devoted to Maitreya, the Buddha of the future, there is also a new magnificent representation of Maitreya there. In addition to the ancient image, there is a modern golden Buddha image that was placed there in 1990 and is called the Buddha for National Unification. It is thirty-three meters tall and covered in eighty kilograms of gold leaf.

Magoksa Temple (Gongju, Chungcheongnam-do)

Located in Chungcheongnam-do, near Gongju, Magoksa Temple dates back to the Three Kingdom period (traditional dates 57 BCE–668 CE) and is surrounded by mountains and rivers. Its setting is not only beautiful, but somewhat inaccessible; and thus, this temple was one of the few not destroyed by the Japanese during the Imjin War of 1592–1598. Most other temples were destroyed and had to be rebuilt after the war, and often at temples, there were fires that destroyed buildings. Some temple complexes have only a fraction of the buildings they once held.

One of the unique features of Magoksa Temple is the stream nearby. It is called Taegeukgang Stream for the shape of the bends of the stream. There the river winds around like the yin-yang circle, called the “Supreme Ultimate” (taegeuk) symbol in Korea. The yin-yang symbol in Korea has mystical powers. The yin-yang theory and the yin-yang symbol were adopted by both Confucians and Daoists in classical China, and spread throughout East Asia. The symbol is important in Korean culture and is even found on the Korean flag today.

Legend has it that the temple was founded by the Silla monk Jajang in 640 although there are those who dispute this claim because Silla Kingdom and Baekje Kingdom, where Magoksa Temple is located, were enemies at the time, just before the unification by Silla Kingdom. The legend also states that Jajang named the temple Magok, meaning flax valley, with the idea that with a temple in this valley, Buddhism would grow rapidly, just like the fast-growing flax plants in the valley.

There are several Treasures (of the second level—National Treasure is highest, Treasure is second, and third are local area designated treasures.) One Treasure is a five-story stone pagoda (Treasure no. 799) that has a top story done in bronze in a style influenced by Tibetan Buddhism. This is said to be one of only five such pagodas in the world. This connection with Tibetan Buddhism shows the international nature of Korean Buddhism. From the earliest days, monks traveled to China and even India, and still today temples host exchanges with monks from other Mahayana lands, and even from the Theravada lands of Southeast Asia.

Magoksa Temple played an interesting role in twentieth-century history. On the grounds of the temple are some Chinese juniper trees planted by the anti-Japanese freedom fighter and president of the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea, Kim Gu (1876–1949), who hid from the Japanese for a time here.

Seonamsa Temple (Suncheon, Jeollanam-do)

Located in Jeollanam-do, near Suncheon, lies Seonamsa Temple, the “Temple of the Rock of the Immortals”—said to have been so named because immortals were known to play baduk (go) on a rock there. In that connection it is one of the three so-called rock temples—with “Cloud Rock Temple” (Unamsa Temple) and “Dragon Rock Temple” (Yongamsa Temple). Am (파일:UKS06 Korea's Religious Places img 3m/) means rock or large boulder. More important, however, Seonamsa Temple is the headquarters and monastic training center for the Taego Order of Buddhism, the married order.

It is interesting that just over the mountain sits Songgwangsa Temple, the main monastic training center for the Jogye Order. At Seonamsa Temple, there are monastics (male and female) who are married—there is freedom of choice to marry or not. Although the celibate order has more monks—they outnumber the married monks by approximately ten to one—there are a significant number of temples around the country that belong to the Taego Order.

Historically, Seonamsa Temple is tied to the famous monk-geomancer Doseon (827–898) of the late Unified Silla period, although it is thought that the site was the location of a hermitage that dates back even earlier, to the Three Kingdoms period.

Seonamsa Temple is characterized as a feminine temple, particularly in contrast to Songgwangsa Temple, on the other side of Mt. Jogyesan, which is a more masculine temple. Certainly, Seonamsa Temple has a warmer, friendlier atmosphere in that the buildings are smaller and closer together with manicured gardens in the various courtyards between buildings.

As one approaches the temple, there is a beautiful stone bridge, like a rainbow in a half-circle formation. It is absolutely beautiful, and the first of two such bridges on the mile-long trail that leads to the temple. Like so many of the major temples, the approach, climbing a path alongside a rippling stream, leads to the temple in a scenic canyon in the picturesque mountains of Korea.

Daeheungsa Temple (Haenam, Jeollanam-do)

On the far southwestern coastal area of Haenam, Jeollanam-do, sits Daeheungsa Temple, also known historically as Daedunsa Temple. Daeheungsa Temple is an old temple said to have been founded in the Baekje period by the Reverend Ado, a monk visiting from the Silla Kingdom in the sixth century. The theme of this temple is the prevention of the three disasters. There are two definitions of the three disasters: one interpretation is disasters caused by nature—fire, flood, and wind. The other definition is disasters caused by mankind—war, disease, and famine.

Daeheungsa Temple has been the home, over time, of many famous masters and national preceptors, and the robes of some of these great masters are preserved in the temple. One of these was the leader of a monk army that fought the invading Japanese in 1592, the monk Great Master Seosan, also known as Hyujeong (1520–1604). Because he led an army of monks against the Japanese, the concept of state protection (hoguk) is invoked at Daeheungsa Temple. Thus, the prevention of disaster, specifically, protecting the country from invaders, is a theme of Daeheungsa Temple.

Daeheungsa Temple has several Treasures and one National Treasure. The main courtyard, also called the pagoda courtyard, is the largest in Korea; thus, the temple has a spaciousness and open feeling. Located on a mountain on the peninsula on the farther southwestern corner of Korea, the remoteness and openness of the temple are striking. Among the buildings of the complex is a hall for 100 Buddhas, and another hall for 1,000 Buddhas.

The most impressive feature of Daeheungsa Temple is the bas-relief carving of the Buddha on a large rock on the compound (National Treasure no. 308). In recent years, to protect the rock from the elements, a large glass enclosure has been built around the rock. Surrounding the Buddha, on the four corners of the large rock are smaller images looking worshipfully at the central image. This rock-carved Buddha, done during the Goryeo period (918–1392), is considered one of the finest of its kind in all of Korea.

Buseoksa Temple (Yeongju, Gyeongsangbuk-do)

One of the oldest temples in Korea, Buseoksa Temple was founded by the famous Silla monk Uisang (625–702). There is a legend accompanying the founding of the temple and the unusual rock formation there that gives it its name—Buseoksa Temple, “Temple of the Floating Rock.” Behind the main hall in the complex is a rock that looks to be suspended over the ground; thus, the idea of its having floated there. The legend says that when Uisang studied Buddhism in Tang China, a maiden became infatuated with him. When he returned to Korea, she transformed herself into a dragon to guard him on the dangerous journey home. Once back in Korea, the spirit of the dragon guided Uisang to build the temple. Once built, the dragon changed into a rock that floated off to the side of the complex to continue its protective spirit over the temple.

The Shrine for the Founder (Josadang Shrine) is a hall dedicated to a portrait of Uisang and is one of the oldest buildings in Korea, dating from the late Goryeo period. A simple structure, yet elegant in its simplicity and antiquity, it escaped the destruction wrought by the Japanese invasion of 1592. Simple in its architecture, it is a testament to the ancient belief system of Buddhism in Korea. In addition to the hall itself as a designated treasure (National Treasure no. 19), there are mural paintings inside the hall that have also been listed as a treasure (National Treasure no. 46).

The main hall, the Muryangsujeon Hall, is National Treasure no. 18. Built in 1376, it is one of the oldest buildings in Korea. The name means “Hall of the Buddha of Limitless Life” and is understood to be a reference to the Buddha Amitayus, another name for Amitabha, the central figure in Pure Land Buddhism, which was so popular in Tang China, and consequently in the Silla Kingdom. After studying in China, Uisang became a great advocate of Pure Land practices along with founding the Hwaeom Order in Silla.

Two more features of Buseoksa Temple are also designated as National Treasures. The Buddha inside the Muryangsujeon Hall, a gilt-clay figure, is no. 45, and no. 17 is a stone lantern in front of the hall. All together there are five National Treasures, as well as additional Treasures and other locally designated artifacts at this temple, making it one of the richest in terms of individually recognized treasures of various levels.

Bongjeongsa Temple (Andong, Gyeongsangbuk-do)

A temple not far from Buseoksa Temple, Bongjeongsa Temple was said to have been located there because the great Silla monk Uisang threw a stone from Buseoksa Temple that landed on the site, and that is where they built the temple, which means “a phoenix’s resting place.” According to tradition, it was built in 672, just after the Silla unification, and legend says it was founded by Uisang. However, a document found at the temple says it was founded by a disciple of Uisang named the Monk of Great Virtue, Neungin.

Bongjeongsa Temple has two National Treasures, and one of the two is especially noteworthy—the oldest building in Korea. The Geungnakjeon, the Hall of Extreme Bliss, a Goryeo-era building from the twelfth or thirteenth century, has that honor. By its title we know it is a hall of an image of Amitabha, again the central figure of Pure Land Buddhism, who also figures prominently in Uisang’s Hwaeom Order. Amitabha had great appeal in East Asia—China and Japan as well as Korea—during the eighth century. Uisang’s study in Tang China led him to study under masters who were captivated by the simple and popular appeal of the worship of Amitabha and rebirth in the Pure Land. Amitabha vowed that he would save anyone who only called his name, and this simplified version of Buddhism had great popular appeal in the spread of Buddhism, particularly in the seventh and eighth centuries and thereafter.

Bongjeongsa Temple is also famous for a recent event. In April of 1999, Queen Elizabeth II of England visited Korea and stopped at Bongjeongsa Temple as the only, and yet representative, site of Buddhism on her trip. She visited nearby Hahoe Village, a classic Confucian village, as well.

In addition to National Treasure no. 15, the Geungnakjeon Hall, there is a newly recognized National Treasure, no. 311, the Daeungjeon Hall, located to its side. Whereas the older hall, the Geungnakjeon, is the hall of Amitabha, the Daeungjeon is the home of Shakyamuni, the historical Buddha who was once Siddhartha Gautama.

Songgwangsa Temple (Suncheon, Jeollanam-do)

Songgwangsa Temple is one of the three jewel temples of Korea. It is the temple of the sangha, the monastery (with Tongdosa Temple the jewel temple of the Buddha, and Haeinsa Temple the temple of the dharma). Today, Songgwangsa Temple is true to its calling as the temple of the monks and the monastery, as it trains more monks than any other temple. The temple is large, with many buildings and a large courtyard and it is remote, located in the far south-central mountains of Korea. The mountain is significant: it is Mt. Jogyesan, named after the dominant order in Korea, the Jogye Order.

Songgwangsa Temple, meaning the temple of the expanse of pine tree, has a deeper meaning. The pine tree refers to eighteen great monks who went forth—the expanse—from this temple. Some authorities consider this the most important temple in Korea because of the monks it has trained and because of its location on Mt. Jogyesan. The most famous monk of the Goryeo period, Jinul (1158–1210), who is recognized as the synthesizer of the Jogye Order, held Songgwangsa Temple as his home. He synthesized two Buddhist factions that had previously argued over the proper way—one side favored texts, the other meditation. Jinul brought both practices together and ended the rivalry that was dividing Buddhism.

Songgwangsa Temple was founded rather late, at the end of the twelfth century, but was built on the site of an earlier Silla temple called Gilsangsa Temple. Some prefer to say that Songgwangsa Temple was founded in the Silla period and changed its name later, but history says the site was unused for a period of time before Jinul chose the location for his home temple.

Three treasures are unique to Songgwangsa Temple. A large rice chest, carved from two tree trunks and looking like a long trough, holds enough rice to feed 4,000 monks. There are twin juniper trees with a swirled pattern of bark on their trunks that are over 500 years old. There is a set of twenty-nine brass bowls that are over 1,000 years old. They have an unusual name—neunggyeon, nansa—meaning “easy to see, but difficult to comprehend.” The name of the vessels is a kind of koan (gongan in Korean), a Buddhist-style riddle used to focus the mind during a meditation session.

The main hall of Songgwangsa Temple has what’s called a double roof—a center section sits atop—it appears—lower sections that stick out at both ends of the upper section. The hall itself holds an unusual set of Buddha images. There is Yeondeungbul (Dipamkara Buddha), a Buddha of light, one bearing a lantern, who is one of the oldest Buddhas; Shakyamuni, the historic Buddha of our era (Siddhartha Gautama); and Maitreya, the Buddha of the future. This represents Buddhas of the past, present, and future.