"Korea's Religious Places - 2.4 Seowon (Private Confucian Academies)"의 두 판 사이의 차이

| 8번째 줄: | 8번째 줄: | ||

Once Neo-Confucianism got its hold on Korea in the early Joseon period, it did not let go throughout the full 500-year history of the dynasty. Another symbol of that deepening interest in the intellectual stimulation of Neo-Confucianism is the spread of the seowon movement. After the founding of the Baegundong Seowon (Sosu Seowon) in 1542, seowon were founded all over the peninsula. | Once Neo-Confucianism got its hold on Korea in the early Joseon period, it did not let go throughout the full 500-year history of the dynasty. Another symbol of that deepening interest in the intellectual stimulation of Neo-Confucianism is the spread of the seowon movement. After the founding of the Baegundong Seowon (Sosu Seowon) in 1542, seowon were founded all over the peninsula. | ||

| + | |||

2017년 1월 4일 (수) 00:24 판

Beginning in 1542, the Joseon period saw a movement that eventually doubled the number of schools in Korea. The hyanggyo were administered by the state, by the local county government, but the seowon were administered by local committees composed of descendants of prominent scholars—descendants both genealogically and intellectually. Indeed, each seowon was dedicated to the memory of one man.

The first seowon was called the Sosu Seowon and was founded by Ju Se-bung (1495–1554), who had traveled to China and saw the school that Zhu Xi (1130–1200) had founded. Zhu Xi’s school was called the “White Deer Seowon” and Ju Se-bung originally called his academy the Baegundong Seowon (White Cloud Seowon), but later the name changed to Sosu Seowon, the “Continue the Polishing” academy. The academy was dedicated to the memory of An Hyang (1243–1306), who is credited with bringing the books of Zhu Xi to Korea and introducing Neo-Confucianism to Korea in the late Goryeo period. Zhu Xi had lived nearly 200 years earlier, in the time of the Southern Song Dynasty (1127–1279), but his philosophy had spread throughout China and Koreans were starting to hear about it. Although it took nearly 200 years for the ideas to spread to Korea, once they did, they took over the intellectual scene in Korea. The Joseon Dynasty, which was founded within a century of An Hyang’s time, was founded on the basis of Neo-Confucian principles. Although it took time, through the first century of the Joseon period, the fifteenth century, Neo-Confucianism came to take over. By the next century, debate on the finer points of Neo-Confucian ideology became the intellectual lifeblood of the dynasty. The two greatest scholars of Korean history, and perhaps the two greatest cultural icons of Korea, Yi Hwang and Yi I, lived in the next century, the sixteenth. The impact of Neo-Confucianism on Korea is perhaps best symbolized by the fact that it is these two scholars who are on the common denominations of money in Korea today, together with King Sejong, who is on the KRW 10,000 note.

Once Neo-Confucianism got its hold on Korea in the early Joseon period, it did not let go throughout the full 500-year history of the dynasty. Another symbol of that deepening interest in the intellectual stimulation of Neo-Confucianism is the spread of the seowon movement. After the founding of the Baegundong Seowon (Sosu Seowon) in 1542, seowon were founded all over the peninsula.

목차

Imgo Seowon (Yeongcheon, Gyeongsangbuk-do)

In Yeongcheon, Gyeongsangbuk-do, one of the first seowon, dedicated in 1553, was built to honor Jeong Mong-ju, the great Goryeo scholar-official who gave his life rather than be disloyal to the Goryeo king, as his colleagues were all getting on board with Yi Seong-gye for the founding of the new Joseon Dynasty in 1392. He was forgiven by the Yi royalty and given posthumous honor as early as 1401. Eventually, he was enshrined in the Seonggyungwan National Academy and this seowon, the Imgo Seowon, was built in his honor.

His loyalty came at the price of his life. He was assassinated because he refused to join the cabal that was setting up to take over power, end the Goryeo Dynasty, and establish what came to be called the Joseon Dynasty. The place of his assassination was a bridge near his home in Gaeseong, the capital of the Goryeo Dynasty. He was killed riding his horse home from a meeting with Yi Bang-won, the son of the founder of the new dynasty, Yi Seong-gye. Legend has it that his blood has permanently stained the bridge, and that when it rains, the bloodstains shine as if they were fresh. Today in Gaeseong, the bridge is one of the most visited sites there. Yeongcheon was the hometown of Jeong Mong-ju and it is there, not far from Gyeongju, that the seowon dedicated to him was built. Interestingly, in front of the seowon, they have built a replica of the bridge in Gaeseong.

In addition, the Imgo Seowon carries one more unique cultural tribute to Jeong Mong-ju. When he was invited to participate in the coup to set up the new dynasty, he rejected the offer, knowing that to do so meant he would die. He allegedly wrote a poem in the classic Korean poetic format called a sijo. It said:

Though I die, and die again;

Though I die one hundred deaths,

After my bones have turned to dust;

Whether my soul lives on or not,

My red heart, forever loyal to my Lord,

Will never fade away.

This poem, memorized by every Korean schoolchild, is written in stone in front of the Imgo Seowon. The poem tells the truth. Though Jeong has been dead for over 600 years, his loyalty lives on in this poem known to all Koreans and appropriately inscribed in stone at the entrance to his seowon.

Oksan Seowon (Gyeongju, Gyeongsangbuk-do)

Built at about the same time as the Dosan Seowon, the Oksan Seowon is dedicated to the memory of Yi Eon-jeok (1491–1553). Yi was a great scholarly innovator in the interpretation of Zhu Xi’s Neo-Confucianism. Many of his ideas exercised great influence on Yi Hwang, who came along a few years later. The Oksan Seowon took nearly nineteen years after the death of Yi Eon-jeok to get built (in 1573). The Dosan Seowon was built three years after Yi Hwang died (in 1574). The late sixteenth century saw the proliferation of seowon, and the rate only increased in the seventeenth century.

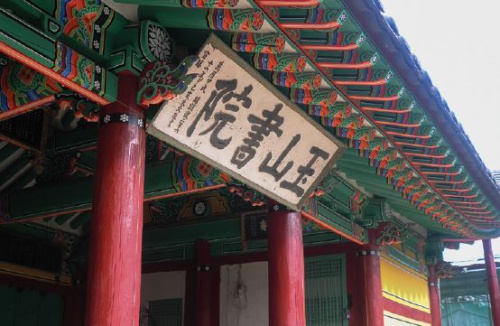

- Oksan Seowon

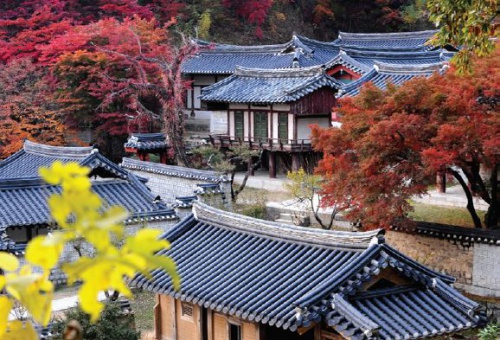

The Oksan Seowon was built in a beautiful setting in a deep wood on the banks of a stream that cuts through a beautiful rock formation. The seowon is next to a small cascade in the stream that lends credence to the unwritten rule that a seowon must be built in a beautiful natural setting.

The seowon, typical of all private academies, has two main buildings, one for teaching and one for ceremonies. Here at the Oksan Seowon, the building for teaching is called the Guindang, meaning “the building for the search of humaneness.” Humaneness (仁, in) is the heart of Confucianism. The Sino-Korean character in (ren in Chinese) is sometimes translated as human-heartedness. It means the relationship between two people and implies all of the moral relationships of Confucianism: king to subject, parent to child, husband to wife, senior to junior, and friend to friend. The hall for ceremonies also has the character in in it; it is the Cheinmyo, the shrine for the embodiment of humaneness. Humaneness is learned (sought) in the school and practiced (embodied) in the hall of ceremonies.

Korean officials are preparing a proposal to have several of the major seowon made into UNESCO World Heritage Sites, but the Oksan Seowon has already been so designated because it was included in the UNESCO inscription of the Yangdong and Hahoe traditional villages. In 2010, these two villages were recognized by the UNESCO organization, and although located about eight kilometers from Yangdong Village itself, the UNESCO proclamation included the seowon as part of the village. This is also true for the Byeongsan Seowon (see p72), located four kilometers from Hahoe Village. Therefore, the Oksan Seowon and the Byeongsan Seowon are already internationally recognized ahead of the other seowon that are in the application procedure at the time of this writing.

Dosan Seowon (Andong, Gyeongsangbuk-do)

In many regards, the Dosan Seowon, built in 1574, is the most important seowon in Korea. It is featured on the KRW 1,000 note, both in regard to its connections with Yi Hwang (1501–1570), who is the historical figure on the note, and because it is the painting of the Dosan Seodang (village school) and its surroundings that is featured on the reverse side of the note. Yi Hwang established the village school to devote himself to study and teaching, and it was elevated to the Dosan Seowon after his death. The Dosan Seowon is probably the most visited Confucian academy as well, even though it is relatively remote and hard to get to. It’s not on the way to any other place; if you go there, it’s because it is your primary destination, and there are numerous visitors.

The Dosan Seowon has one feature different from most: it was built on the grounds of the scholar’s residence. Most seowon are located in picturesque locations, somewhat removed from villages and residences. Not the Dosan Seowon. While the setting is picturesque, it is on the very site of the residence of Yi Hwang, built just behind the house where Yi Hwang once lived and taught. In fact, one of the more striking aspects of this site is Yi Hwang’s humble home. It is not large by any stretch and bespeaks the antimaterialism of Confucianism. But the interesting thing is the addition to the porch of his house—the extension of the porch and of the roof over the porch so that another six or eight students might sit and study with the master.

- Dosan Seowon (left) and a distant view of Sisadan Stele from the seowon

The Dosan Seowon, like the house of Yi Hwang, is of a humble scale. The educational buildings and dormitories behind the house are smaller than those found at most seowon, and the facilities are somewhat crowded onto the hillside behind the house. The earlier Sosu Seowon is set in the bottom of a valley, on the banks of a stream, and has open spaces. But the Dosan Seowon is set on a steep hillside where one climbs stairs to the house, more stairs to the school, and up a steep set of stairs to the shrine. The scene to the front is beautiful today because it overlooks the reservoir created by the Andong Dam, but traditionally it overlooked a beautiful valley.

Piram Seowon (Jangseong, Jeollanam-do)

At the same time that Ju Se-bung, Yi Hwang, and Yi Eon-jeok were flourishing in the Gyeongsangbuk-do area in southeast Korea, and in Jeolla-do in the southwest, Kim In-hu (1510–1560) was leading scholarship on Neo-Confucianism in his region. Eventually, Kim In-hu became one of the eighteen sages enshrined at the Seonggyungwan National Academy in Seoul. He was the only scholar from the southwest to be so honored.

The seowon dedicated to him, the Piram Seowon (sometimes romanized Pilam) was dedicated in 1590, just after the early seowon created in the Gyeongsang-do region. It is located in the heart of the Jeolla-do province area in Jangseong, near today’s regional capital, Gwangju.

Architecturally, one is first struck by the imposing gatehouse at the entrance. The gate building is a large, two-story building with an upper floor and open deck that provides space for discussions as well as a commanding view of the whole complex. Untypically, however, the gatehouse is colorfully painted, almost reminiscent of a Buddhist structure. The rest of the complex is more traditional in its plain paint.

- Gwagyeonnu Pavilion (left) and Cheongjeoldang Lecture Hall of Piram Seowon

Arranged in the typical school-in-front, shrine-in-back orientation, the courtyards and open areas are more spacious than those at most seowon. There is a large courtyard inside the gatehouse before one reaches the school building. Although the school is in the front, the dormitories are in the courtyard behind the school; whereas, at most seowon, the dormitories are in the courtyard in front of the school.

In the school courtyard, there is an extra building to house wood engravings (blocks engraved with a painting of bamboo) bestowed by King Injong. The building has an added feature: the signboard for the building was calligraphed by a king, King Jeongjo (r. 1776–1800). This speaks to the method of honoring Confucian scholars. Kim In-hu died in 1560, the seowon was dedicated in 1590, and the king sent a signboard 200 years later.

The ritual space, as with most seowon, is separated from the schoolyard with a wall and a three-door gate. The building that houses the spirit tablet of Kim In-hu is relatively small; in fact, it is only slightly larger than the structure built to house the engravings given to the seowon by the king.

Byeongsan Seowon (Andong, Gyeongsangbuk-do)

The Byeongsan Seowon is located near Hahoe Village, which together with Yangdong Village was recognized by UNESCO in 2010 as a World Heritage Site. The scholar-official honored in the Byeongsan Seowon is Ryu Seong-ryong, who was the prime minister during the Japanese Invasion of 1592.

The most striking thing about the Byeongsan Seowon is its namesake. Byeongsan means screen mountain, which means that the mountain looks like a standing screen, such as one finds set up in a home, with eight or ten panels, with art or calligraphy on each panel. Indeed, on the far side of a gentle curve of the Nakdonggang River stands a mountain ridge of uniform height that undulates in and out, just like a standing screen. In harmony with the mountain on the opposite side of the river, stands the seowon facing the center of the mountain screen with a long building facing the mountain, mirroring the reach of the mountain from side to side, longer than most premodern buildings. But the beauty of the building is the second story, an open-air pavilion where one can sit and discuss some arcane doctrine, recite poetry, or just look out at the beautiful river and mountains.

One enters the compound through a three-tier gate, but it only has one door. This is a bit unusual because almost all such shrines have three doors. Inside the gate, one walks through the bottom floor of the two-story pavilion and climbs stairs into the main courtyard. Behind you now is the upper deck of the pavilion, open on all four sides with a great view of the surrounding scenery. The rest of the compound is like other seowon, with lecture halls and dormitories on the sides, and the ritual space behind the school. One variation might be worth mentioning. While most seowon, like nearly all hyanggyo, are lined up on a central axis, the shrine space at the Byeongsan Seowon is off-center to the right, as is the shrine at the Dosan Seowon. But at the Oksan Seowon and most seowon that developed later, symmetry is the rule, with the main buildings lining up on the central axis.

- Byeongsan Seowon (left) and its Ipgyodang Lecture Hall

The main figure enshrined here is Ryu Seong-ryong, who, as prime minister, helped guide Korea through the perilous years, 1592–1598, of the Japanese invasion. His diary is one of the treasures of Korean historians; wherein, he recorded in detail Korea’s fight against the invaders.

Donam Seowon (Nonsan, Chungcheongnam-do)

The Donam Seowon was built to honor the great scholar Kim Jang-saeng (1548–1631) in 1634. In 1660, King Hyeonjong calligraphed the signboard to hang at the main hall. The royal signboard made the Donam Seowon one of the protected seowon that were not destroyed or downgraded during the rule of the Heungseon Daewongun, who, as regent for the king in the 1860s, recognized only forty-seven seowon.

Most noteworthy at the Donam Seowon are the scholars enshrined there. In addition to being the primary seowon to honor Kim Jang-saeng, there are three other major figures enshrined here. Altogether, these four scholars are also enshrined in the Seonggyungwan National Academy. The only father-son pair enshrined at the Seonggyungwan National Academy is Kim Jang-saeng and his son, Kim Jip—Kim Jip is also enshrined here at the Donam Seowon. The other two from the National Academy were distant cousins, Song Jun-gil and Song Si-yeol.

More than their physical features, the buildings, or National Treasures, at this seowon, the unique feature is the family connections of the great sages honored here—two are father and son, and two, although not close family, are from the same lineage. None of the other sages are of the same lineage.

Song Si-yeol is particularly noteworthy. Of all the scholars enshrined in the National Academy, he wielded the most political power. The eighteen honored scholar-officials were more noted for their scholarship than for the particular political office they held. None was a prime minister, with one exception—Song Si-yeol. He not only had the highest office in the land, he held office longer than any other official of those honored in the National Academy or not. He served as prime minister to five kings, holding the highest office longer than any other official. In the end, his political enemies convinced King Sukjong, who was then only fifteen years old, that Song should be driven from office and sent into internal exile. Song’s friends came to his rescue, and he was ordered released and allowed to return to Seoul. However, Song’s enemies rallied and opposed the release, and in fact came up with stronger indictments, such that the manipulated boy-king ordered Song’s execution.

Song was on the way back to Seoul when the king’s messengers arrived with the bestowal of death—the poison for Song to drink, all bottled in fine porcelain and boxed in fine lacquerware. Song was no mere bureaucrat. It was his understanding and writing about Neo-Confucianism that got him installed in the shrine at the Seonggyungwan National Academy, and in several seowon, like the Donam Seowon, around the country.